No, it’s not clickbait. I meant what I said.

It's a common belief that people have set learning styles - some are visual learners who absorb information best through charts, and others are auditory learners who prefer lectures and podcasts. This idea is so prevalent that it's often taken as established fact in education.

You've likely even been asked yourself about your specific learning style. However, an extensive body of research has revealed that this belief in different learning styles is not supported by evidence. This pervasive myth is more than just harmless pseudoscience - it can actively impair effective teaching and learning when put into practice.

In classrooms, belief in learning styles has led many teachers to try to present lessons in different modalities to cover all the styles. They strive to serve auditory, visual and kinesthetic learners. In reality, research shows that label provides no benefit.

In technology, it has led to products marketed around catering to different styles, despite no proof this improves outcomes. While personalized learning is a worthy goal, pigeon-holing students based on pseudo-scientific learning styles is not the way to achieve it.

What are learning styles?

The origin of learning styles theory can be traced back to experiments by psychologists like Howard Gardner and Neil Fleming showing apparent differences in how students retained visual versus verbal information. Though these early studies had small sample sizes and questionable methodologies, the basic concept took hold.

The appealing notion that everyone has a specific mode in which they optimally learn seemed intuitively right. People do report subjective preferences for how they like to receive new information. But a preference does not equate to a style that determines learning ability.

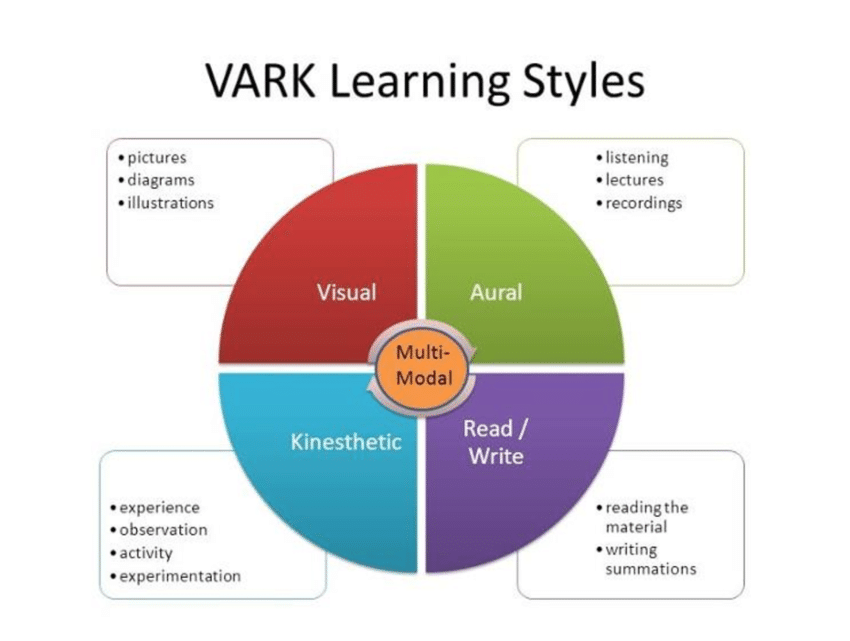

The concept of learning styles theorizes that individuals each have an optimal way of absorbing new information, whether it be visually, verbally, physically, logically, socially, or through some other mode. While definitions vary, one of the most common frameworks categorizes learners as:

Visual Learners - These learners supposedly process information best when it is presented visually, such as through images, diagrams, charts, demonstrations, or reading. They benefit most from seeing the content.

Auditory Learners - These learners are believed to learn better through listening methods like lectures, discussions, podcasts, and oral instructions. They get more from hearing content.

Kinesthetic or Tactile Learners - These hands-on learners are said to prefer physically interactive modes like manipulative models, touching and working with materials, or taking notes. They gain more through active physical engagement.

Various questionnaires and assessments have been developed to supposedly determine an individual's dominant learning style, though their scientific validity is questionable. Styles are sometimes expanded beyond those three main types to include verbal, logical, social and solitary preferences. They are also frequently conflated with simplistic notions of left-brain versus right-brain dominance.

The Case Against Learning Styles

Despite the lack of evidence, the intuitive appeal of learning styles makes them persist. When a student says "I'm a visual learner," it resonates with a subjective feeling that they learn better when they can see things rather than just hearing a lecture. But studies show these stated preferences do not reliably predict actual learning aptitude across content types.

A 2008 review published in the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest concluded that the learning styles concept had a “trivial” impact in experiments and no evidence of generalizable benefits.

In one example, students were asked if they preferred visual or verbal learning. They overwhelmingly selected visual. However, in follow-up tests, there was no correlation between that preference and their ability to recall information presented visually versus verbally. Just because someone thinks they have a visual style does not mean visual lessons optimally boost their learning.

“There is no credible evidence that learning styles exist,” write psychologists Cedar Riener and Daniel Willingham in their 2010 paper The Myth of Learning Styles. “Students may have preferences about how to learn, but no evidence suggests that catering to those preferences will lead to better learning.”

Perhaps most damning, in a 2010 study from Indiana University, students were assigned by their supposed learning preference and then tested across different material types. Visual learners did no better on visual tests than verbal ones, nor did auditory learners show strength with auditory information. This well-controlled study experimentally confirmed that matching instruction type to learning style showed no advantage.

Multiple comprehensive reviews of the scientific literature on learning styles have been conducted over the years. In a 2004 review, professors from the University of Virginia found that less than 5% of studies provided any evidence for the effects of matching material to learning styles.

Proponents argue that using multiple modes tailored to styles keeps students more engaged and motivated, leading to better outcomes. But research finds engagement stems more from providing content variety, novelty, and context - not matching mythical styles. Good teachers adapt to learner needs, but assigning lasting styles with any certainty after a test or survey is not empirically warranted.

While no one denies people have personal preferences, the science is clear that learning styles are not real innate traits with defined educational implications. Unfortunately, misunderstanding of styles persists in many learning environments. Dispelling this myth will require a better public understanding of the evidence against it.

Dangers of the Learning Styles Myth

Though the learning styles concept is appealing in its simplicity, putting it into practice in education carries significant dangers:

Wasted time and resources: Teachers spend valuable instructional time administering learning style assessments of questionable validity. Effort goes toward designing lessons for disparate styles rather than proven methods. Schools devote limited budgets to ineffective learning style products.

Potential mismatches: Ironically, pigeonholing students into rigid styles may result in more mismatching between material and student aptitudes. A student labelled an auditory learner may miss out on powerful visuals that could aid understanding. Assumed styles may become self-fulfilling prophecies that inhibit growth.

Constraints on personalization: While personalized education is important, learning styles limit it to superficial traits rather than meaningful differences in developing skills and interests. Constraining students this way hinders response to their real individual needs.

Student stereotyping: Reducing learners to simple style labels can lead to damaging stereotypes. Evidence shows even well-intentioned stereotyping can negatively impact student outcomes according to racial, gender, cultural or other biases.

Neglect of actual science: Focus on the pseudoscience of learning styles distracts from cultivating teaching and learning grounded in research on cognition, motivation and skill development. Valuable principles from cognitive science get overlooked.

Commercial exploitation: The prevalence of learning styles helps edtech companies market products lacking scientific validity. Product claims based on flaky science should face far more scrutiny to protect students.

Learning styles may seem harmless, but implementing invalid assumptions in classrooms carries real risks. Moving forward requires concerted efforts to leave ineffective practices behind.

Why the Myth Persists

Given the lack of evidence and potential harms, why does belief in learning styles continue to be so widespread in education? Why do 80-95% of people still believe in it? Among the reasons:

Confirmation bias: When teachers use learning styles, they often believe they see improved outcomes. However, research shows this perception is subjective confirmation bias, not empirical gain.

Neuromyths: Misinterpretations or oversimplifications of neuroscience, like left brain/right brain theories, propagate learning styles and other neuromyths. Many find brain-based explanations compelling. A survey conducted in 2017 highlighted the widespread acceptance of learning style neuromyths among educators. The study polled 598 teachers to gauge belief in common pseudoscientific ideas about learning and the brain. Alarmingly, 76% of respondents agreed with the statement that students learn better when lessons match their preferred learning style. Additionally, 71% agreed that children have dominant sensory learning styles, such as auditory or visual.

Commercial interests: Edtech companies, assessment organizations, and consultants financially benefit from the learning styles concept. They continuously market pseudo-scientific products and services for profit.

Conceptual appeal: Categories like visual and auditory feel intuitively correct. People conflate preferences with styles. The idea resonates even though evidence does not back it up.

Teachers’ desire to help: Educators want to support students. Learning styles offer a seemingly easy way to identify needs. But this desire leads to the adoption of ineffective practices.

Lack of scientific literacy: Both pre-service and in-service teachers often lack training in scientific methods and critical thinking to identify unsupported claims. In more than half of U.S. states, teachers are required to study learning styles theory as they prepare for high-stakes licensure exams and this is the case with many other countries.

Cognitive biases: Cognitive scientists suggest it stems from a natural human tendency toward “essentialism” - the intuitive bias that people have deep-seated, stable traits that categorize them. We essentialize gender, race, personality and more in ways that often reflect biases rather than objective facts. Evidence shows essentializing learning this way similarly lacks a scientific foundation, despite feeling subjectively true. The learning styles concept also provides an appealing marketing narrative for education products aimed at different types of learners.

Countering the learning styles myth requires recognizing these psychological and commercial factors that allow it to persist.

Moving Beyond Learning Styles with Edtech

While belief in learning styles remains prevalent, the path forward is not unclear. Effective personalized learning is possible without reliance on debunked concepts. Edtech can play a pivotal role through:

Adaptive learning platforms: Rather than assign static styles, the software can adapt in real-time to each student's developing skills and knowledge. Algorithms analyze patterns in learning data to optimize lessons, not unproven labels.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL): UDL frameworks guide the creation of flexible digital tools accessible to diverse learners. Multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression are built in without limiting styles.

Metacognitive reflection: Edtech prompts can encourage students to think about their own learning process through reflection. This develops self-awareness, not constraining categories.

Multimodal content: Digital content like videos, simulations, and interactive elements can present the same material through different modalities tailored to natural variations in developing abilities and interests.

Student empowerment: Learner dashboards give students access to their own learning data to take ownership. They can find optimal study strategies, not be told their one style.

Teacher professional development: Effective PD helps teachers implement personalized edtech in their classrooms and avoid pitfalls like learning styles. Teachers must stay current on the science.

With the right evidence-based principles, edtech can enhance instruction for all types of learners in all their diversity. The learning styles myth fades away when products focus on real needs, not pseudoscience.

Recommendations for Educators

Edtech has a role in leaving learning styles behind, but teachers are critical in executing effective learning strategies grounded in science. Educators should:

Evaluate products skeptically: Before purchasing an edtech tool or curriculum claiming to cater to styles, scrutinize the evidence. Demand proof it improves outcomes.

Focus on Universal Design for Learning (UDL): UDL provides guidelines for maximizing learning for all types of students through flexible methods, materials, and assessments. This avoids limitations of learning styles.

Use technology to promote metacognition: Have students use edtech features to reflect on their learning process. Guide them in thinking about their own cognition.

Develop study strategy skills: Help students identify effective strategies through metacognitive work and analysis of their learning data. Adaptive tech can assist in strategy development. Teach students how to learn.

View learners as individuals: Get to know students' skills, interests, motivations and developing abilities. Respond to them as individuals, not learning style categories.

Stay current with learning science: Seek professional development on evidence-based personalized learning strategies. Maintain awareness of debunked neuromyths that still propagate.

Grounding practice in scientific research and understanding each learner's needs will lead to truly personalized, effective instruction for all.

In A Nutshell

It’s not how we learn that determines what we learn. It’s what we learn that determines how we learn. If you want to learn how to play football/soccer(the beautiful game), playing it will be a lot more effective than reading about it, whether you are a kinesthetic learner or not.

The enduring popularity of learning styles theory serves as a powerful example of the danger of neuromyths in education. While the concept has intuitive appeal, decades of research and meta-analyses definitively show no benefit to classifying students by supposed learning styles and designing instruction based on those labels.

Not only is the practice ineffective, but it can be detrimental by constraining real personalization, promoting stereotyping, and leading to misapplication of limited resources.

For students to reach their full potential, practices not supported by empirical evidence have no place in modern instruction, whether physical or digital. With better application of learning science and technology, personalized education's true possibilities can be achieved. The time has come to leave the learning styles myth behind.

Thanks! I also think you are doing amazing work. It is nice to find someone else on Substack heading in a similar direction. Thanks for the recommendation. We will have to team up sometime in the upcoming months. I tend to be a little more cautiously excited about the AI future. But I think our viewpoints harmonize nicely. Let me know if you need any assistance or resources. I’d be happy to help in any way I can. http://linkedin.com/in/nick-potkalitsky-phd-0313ba126

Have you read NeuroTeach: Brain Science and the Future of Education? It has a lot of good brain-based evidence that disproves learning styles theory.

Thought you might be interested.

Great post!